🧠 Deep dive — 3 steps to go from "we can't" to "we can if"

It’s common to feel stuck with no good choices, but we usually aren't. Here's a 3-step reframing process to force your brain into creating some choices when you feel you have none.

Hey friend 👋

When you have exhausted all possibilities, remember this: you haven’t.

— Thomas Edison, noteworthy inventor

It’s a common problem to feel stuck, and that there are just no good choices.

This is usually wrong. But saying so is about as helpful as telling someone “don’t panic”, so I’ll let you in on a little secret…

There’s an ideation process I use all the time to force our brains into creating some choices when we feel we have no choices to make.

Let’s dive deep 👇

The guiding philosophy is the same as Captain Kirk’s:

I don’t believe in no-win scenarios.

The trick is to uncover hidden possibilities in what seem like no-win scenarios by imagining what it would take in this scenario to win.

From:

We can’t X!

To:

We can X if…

It’s not a gimmick. It’s a tool.

We too often leave many paths completely unexplored because our internal filter prematurely tells us they aren’t doable.

By shifting from a mindset of “we can’t” to “we can if”, we discover there are a multitude of available options and some interesting (and completely unexpected) ways to get there.

Unfortunately… this is easier said than done, so let’s get to work:

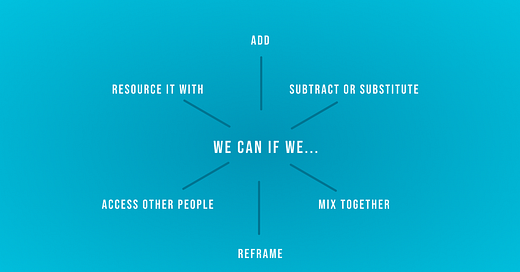

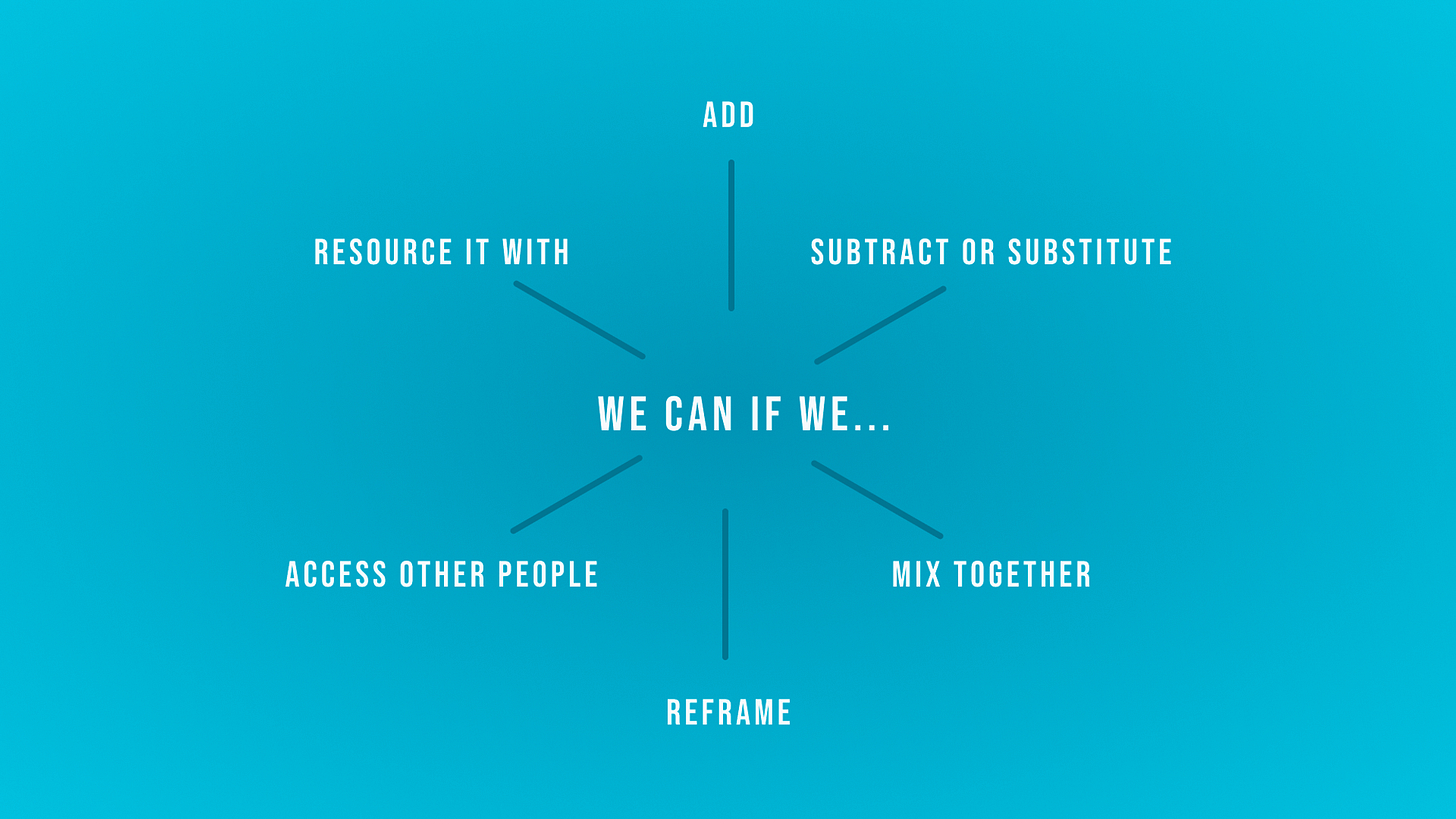

There are six “we can if” possibilities.

Take any situation that feels no-win, where you’d say “we can’t”, and start a sentence with “we can if”:

We can if… we add…

We can if… we remove or substitute…

We can if… we mix together…

We can if… we think of it as…

We can if… we access other people to…

We can if… we resource or fund it with…

These are 6 different ways to crack open the door of possibility to find a path forward.

These six options are designed to get around our built-in filters by ignoring the “how” question — that comes later.

Quantity before quality.

Creating choices before making choices.

Divergent thinking before convergent thinking.

But… these can feel a bit vague until you get used to it, because they’re high-level. So let’s break each one down:

1. We can if we add…

The central question is about what’s missing.

We could get out of this sticky wicket if we only had something that we don’t have. It’s easy to self-censor and filter out the ideas that fall into this bucket, because we’re starting with the premise that it can’t be done because we don’t have the thing.

But by asking the question, we can often think of parallels or analogs. And, if we can’t, it shifts the question to another we might be able to answer: we can do X if we can get Y, so how do we get Y?

For example, we can if we add…

… new features.

… more support.

… innovative solutions.

… diverse perspectives.

… extra incentives.

What could you conceivably add in order to hit the target?

2. We can if we remove or substitute…

Sometimes, it’s more about obstacles.

We’re in this jam and can’t find our way out because we’re stopped by X. This is fundamentally the same as the addition, in that our focus can shift into how we remove the blocker.

For example, we can if we remove or substitute…

… unnecessary steps.

… outdated methods.

… costly elements.

… inefficiencies.

… complex procedures.

… barriers to entry.

What could you conceivably remove from the process in order to make the goal more attainable?

3. We can if we mix together…

Sometimes it’s not at all about adding things or removing things, but about finding new ways to apply what we already have.

Can we combine things together — cobbling them together, if necessary! — to make it achievable?

For example, we can if we mix together…

… different ideas.

… various skill sets.

… multiple technologies.

… unique perspectives.

… complementary products.

… distinct methodologies.

Looking at what we have access to, how can we hack something together to help us hit the target?

4. We can if we think of it as…

And now for my favourite — the reframe!

This is the most powerful and least utilised of the “we can if” questions. Very often, we can create new choices simply by asking the question in a different way.

For example, we can if we think of it as…

… an opportunity.

… a challenge to overcome.

… a learning experience.

… a game or puzzle.

… a partnership.

… a creative process.

How can we reframe the question in a way that creates a target we can hit, or at least better understand?

5. We can if we access other people to…

Team is everything — and it’s much broader than just your founding team. It’s your employees, board, advisors, investors, customers, and other stakeholders. I’ve written about this before.

A fantastic way to open up new options is to expose the problem to more people.

For example, we can if we access other people to…

… share expertise.

… provide feedback.

… offer support.

… promote the idea.

… collaborate on solutions.

… invest resources.

When in doubt, how can you get more people in the room, and what can you ask them?

6. We can if we resource or fund it with…

And we end with the one everyone jumps to: money!

Sure, more money solves a lot of problems — maybe most problems. But it’s rarely the tool you should reach for first. Buying your way out of hole is often just a quick way to make the hole deeper. But it definitely has its place, because, well… money buys stuff.

But it’s not always about cash.

For example, we can if we resource or fund it with…

… additional funding.

… new technology.

… skilled personnel.

… strategic partnerships.

… dedicated time.

… innovative tools.

What resource, if we had it, would make hitting the target more likely?

Here’s how to put it into practice.

It’s not complicated:

Step 1: Use “we can if” to identify a bunch of potential paths.

This is the hardest part, because our internal critic has already suppressed it. Our mind has already told us “no”, but we can use the six prompts above to push through. The goal is quantity over quality.

As an example, perhaps we can get out of the quagmire if we fund it with more money.

Step 2: Ideate around how each potential path could work.

The biggest mistake you can make here is to re-activate that internal critic and say “no, it’s not possible”. But we’re still ideating here. We’re still engaged in divergent thinking.

Let’s continue with the funding example. It would be easy to say, “but we don’t have money”, and then nix the idea.

But there are 7 ways to get money:

You can have it.

You can earn it.

You can borrow it.

You can trade equity for it.

You can steal it.

You can commit fraud.

You can mint it.

Hopefully some of those are off the table for you, but this is a judgment-free zone. For the remaining options, what would a couple of ideas for each look like?

Create some choices, but don’t make a choice yet.

Step 3: Filter down to pick the most efficient option.

You’re almost there! You’ve got a bunch of options. The “quantity” part is done. Now, it’s time for “quality”.

Efficiency, as I’m using it here, is a measure of impact and challenge. You can check out this matrix I created to get a visual representation.

Which of the options you surfaced would be both really impactful and would be relatively low challenge to implement?

That’s where you make your next move.

And that’s it! In three steps, we’ve gone from a no-win scenario to a viable plan of attack. And it works almost every time.

All that’s left?

But what if there really are no choices?

We often treat the problems we encounter as things we have to fix, solve, or get rid of.

And sometimes they are, but it’s a fairly limiting way of looking at the scope of potential options.

Sometimes, the problems we encounter aren’t stop signs: they’re new rules of the road — aka constraints. There’s an extraordinary hidden superpower in learning to leverage — and even love — constraints. They transform limitations into opportunities, forcing us to be creative.

Constraints are like the narrow banks of a river, creating the focus and potency needed to guide and accelerate us toward powerful, innovative breakthroughs.

But that’s another post.

See you next week, my friend.

—jdm