🧠 Deep dive — Slow Startup Suicide: how to kill your startup and never know why

Solving a big, important problem isn’t enough. In this Traction Deep Dive, I’ll share the greatest determining factor of startup success, and give you a tool you can use to crush it.

Hey friend 👋

Welcome to my new Thursday newsletter — Traction Deep Dives!

Each week, I’ll pick a topic on startups and traction and go in-depth, with original analysis, insight, and how-to. It’s not just theory. These deep dives will always have actionable info that you can put to work in your startup today.

So pour yourself a cup of coffee — or, a glass of wine (I won’t tell) — because I’m gonna squeeze your brain like a stress ball.

Let’s go.

Solving a big, important problem isn’t enough to make a startup successful.

This might seem counterintuitive.

It’s common for startups to gravitate towards solving large problems, assuming customer pain is what’s valuable. However, not factoring in the urgency of the problem can lead to a phenomenon I describe as ‘slow startup suicide’ — a scenario I’ve witnessed too often.

In this Traction Deep Dive, I’ll share the single greatest determining factor of startup success, and give you a tool you can use to crush it.

Let’s dive deep. 👇

But first, the common tale of slow suicide.

You’ve probably heard this story before.

You explore a problem, and find tons of customers have it. Traction tests are positive. Rapid prototyping goes brilliantly. Everyone wants it solved, and they love your solution. So you build it.

And no one buys.

Puzzled, you mess with the offer. You explore different business models. You tweak the pricing, placement, and value proposition. Many, many times.

And still… no one buys.

So you go back to the drawing board. You talk to customers, and the problem is still big, and they’d still love a solution, and they still love your solution.

And yet… no one buys.

WTF is going on? 🤯

Customer pain is tempered by lack of urgency.

Startups get pricing wrong and develop weak value propositions because they don’t understand this fundamental principle of offer design.

It’s slow startup suicide.

If you’ve been following me for a while now, you know I love little models. If you’ve ever spent time in a room with me, you’ll know I often leave little illustrations, like bones strewn in the lair of a hideous monster.

And so, of course, I have a little model for this, too:

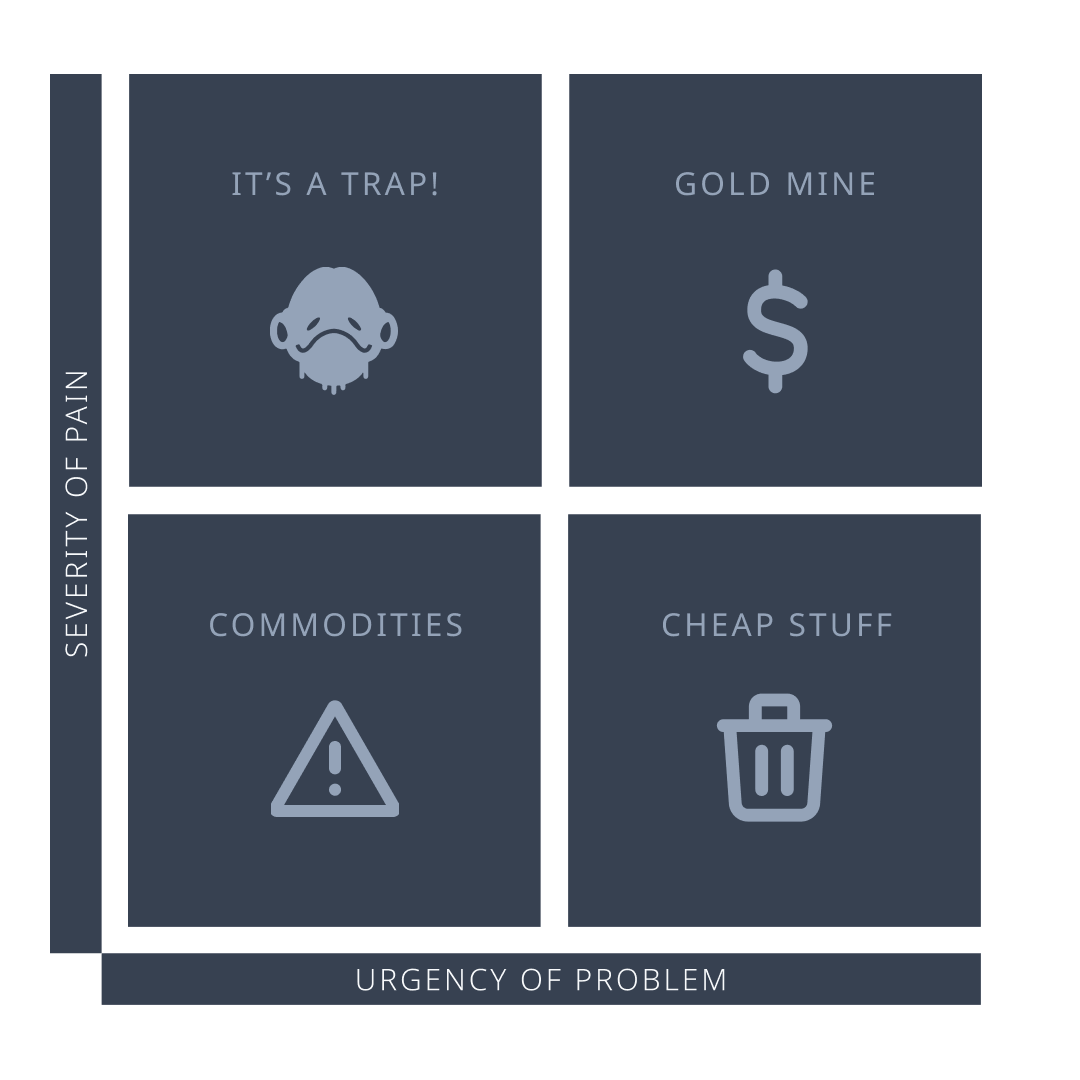

It’s a simple 2x2 grid to visualise the relationship between severity and urgency in a customer value proposition.

On the Y axis, we have the severity of the pain. The higher up, the more painful the problem is.

On the X axis, we have the urgency of the problem. The farther to the right, the more important it is to solve the problem right now.

And that leaves four basic quadrants:

Low severity, low urgency. Commodities.

Low severity, high urgency. Cheap crap we have to buy anyway.

High severity, high urgency. Freakin’ gold mines.

High severity, low urgency. The slow startup suicide.

Let’s break each down.

Low Severity, Low Urgency.

These are commodity products.

We may need them, but they don’t solve an acute pain, and we don’t feel much, if any, urgency in solving it. It’s not that we aren’t interested in the problem, but we’re not that interested in the problem.

Commodity products are easy to replace, tend to have low loyalty, and are typically priced to reflect their relative unimportance. Consumers of these products tend to be fairly price-sensitive.

For competitors, it’s a race to the bottom. Avoid this space.

Low Severity, High Urgency.

These are items we need, but don’t value very much.

We need them, and we need them now, but we don’t care much about them. They certainly don’t relate in any way to our identity, and we have no particular loyalty to the solutions offered. Think toilet paper.

Sometimes, they’re just acquired ad hoc, as needed, and we choose based on what’s on the shelf in our moment of need — right place, right time products. Little more.

This is typically garbage. Even disposable. Sometimes perishable.

Proceed into this quadrant with extreme caution.

High Severity, High Urgency.

These are friggin’ gold mines. 💰

They’re big problems that need solving right now, and customers pay a premium to solve them.

Products that address these needs are often unique — which is why it’s them that are needed. They’re difficult to replace, because they solve the problem better than the alternatives (if alternatives there be).

All startups should focus on solving these problems.

High Severity, Low Urgency.

This is where startups go to die.

Customer discovery reveals the pain, and it’s a big pain. All of your validation shows they want to solve it, and that they like your solution.

On the surface, it looks like an amazing opportunity!

But…

No one has only one problem. We all have 10 problems in our lives, but we lack the bandwidth to solve them all, and we put in no effort to solve the 10th most important one. We want to solve it… but someday.

It doesn’t matter if a problem’s big if there’s no urgency to solve it.

Sure, it’d be nice to get it solved. But there are so many other priorities that the pain of solving it has not (yet) been eclipsed by the pain of not solving it. I see this all the time with early-stage startups:

All of the customers you get in front of are annoyed at the problem and excited about the solution, but they don’t buy! They talk a good game, and then they say “not now” — or even ghost you.

You killed your business, and you never learn why. That’s why I call it the slow startup suicide.

Because you’re solving the wrong problem.

It’s crucial during value proposition design to understand the relative importance of customers’ needs, wants, and fears.

The mistake many founders make is equating importance with the severity of the pain. That’s a good starting point, but it’s more than that. Importance is a measure of severity and urgency.

So solve the problems your customers really want solved — right now.

Here’s how to put this to work

Grab your sticky notes and a whiteboard (or FigJam) and draw the above grid. Severity on the Y axis, urgency on the X axis. Four quadrants.

Jot down each problem your customer has on a sticky note. Get them from your value proposition canvas, or think of their needs, wants, and fears. Go back through your customer interviews and familiarise yourself with how they described their lives.

And then, hold each sticky note, one at a time, at the dead centre of the grid. Then ask your team: higher or lower? Left or right?

Keep discussion to a minimum, because the answer isn’t in your head. If you don’t have the data, go get it. There are no facts inside the building.

Once you have all the stickies placed, grab the one highest and furthest to the right.

Then ask: how might we solve it?

Because if we can, this combination of severity and urgency leads to “market pull”: if you set the offer down on the table, customers leap at it without discussion. It sells itself.

Those are the unicorn products.

—jdm