🧠 Deep dive — ditch aimlessness and set clear goals for 2024

Make goals foolproof with the GSM framework.

Happy New Year! 🎊

As the first Deep Dive of 2024, what better topic than goal-setting? Let’s get right to it:

Startups often wander aimlessly.

The problem isn’t effort, grit, or guile. And it isn’t because they’re not setting goals.

It’s that they’re setting the wrong goals.

That’s where the Goals Signals Metrics (GSM) framework comes in. It’s not just a tool; it’s a beacon, guiding startups to identify the right metrics at the right time that align with their goals.

Today, I'm talking about how the GSM framework can be your guide in establishing a focused, data-driven path for your startup.

Let’s dive deep 👇

Let’s start with an obvious truth:

One of the greatest predictors of startup performance is knowing what to measure.

It provides a clear plan of action of what to do today, and it provides data to show if that action is successful, which, in turn, helps us figure out what we’ll do tomorrow.

Or, to resort to cliché: what we measure is what we improve.

Unfortunately, startup measurement is really hard, and, though I’m not sure why, measurement is not something we teach founders.

The result?

Most startups have crappy goals.

Often, they’re not measurable. Many startups espouse broad, overly-inclusive goals like “finding customers”.

But abstract goals aren’t actionable.

Other times, startups measure the wrong things. Commonly, early-stage startups will eye revenue before their value proposition is tested, which will almost guarantee missing the mark and wasting precious time and money.

This is a common theme in my advisory work.

While I wouldn’t deign to tell you what your startup’s goals should be, I can give you frameworks that you can use to create targets that drive results.

The best framework? Goals, Signals, Metrics.

Academically, the Goals Signals Metrics (GSM) framework is a strategic management tool designed to align your objectives with measurable outcomes.

It’s a 3-tiered hierarchy:

Goals represent your high-level objectives, reflecting your startup’s mission and strategic priorities.

Signals are indicators that suggest you’re on track — qualitative predictors of success or failure.

Metrics are quantitative measures used to assess specific performance against your signals and goals.

The GSM framework facilitates a purpose-driven, goal-oriented focus at the high level, while promoting organisational learning and being highly adaptable to change — which is something startups experience a lot of. 😅

Goal-setting isn’t not about knowing exactly where you’ll be in three years and setting a metric to track it.

GSM is about being directionally accurate:

Success is… over there somewhere.

Success is not… all other directions.

But by balancing qualitative and quantitative analysis, and through chaining leading indicators together, it tells you if you’re on the right track, and provides a system for changing it when you’re wrong.

When you’re wrong. 😬

This is the basis of innovation accounting.

GSM gives you all this, while also providing the benefits expected from any goal-setting framework (e.g. BSC, OKR, ToC, etc.):

improved decision-making;

increased accountability;

early detection of problems;

more alignment within the team;

enhanced communication and clarity;

and more.

But enough theory…

Here’s how to use it.

Setting up Goals Signals Metrics within your startup is actually a fairly straightforward enterprise, if you start with a good hypothesis.

In fact, it’s only three steps:

What is the big goal?

What are the signals (leading indicators) that you’re the right track?

How can you measure those signals?

That’s too high-level to be actionable, so let’s break it down:

1/ What is the big goal?

It may be the best way to get somewhere you’ve never been, but the worst way to try to get where you want to go is to not know where it is you want to go.

Duh.

At the highest level, your goal is a scalable startup. That means you need what I call a “credible theory of hugeness”:

It has to have the potential to get really huge;

You’re not huge yet, so need a theory of how you’re going to get huge;

That theory is only worth anything if it’s a credible one.

At the highest level, your goal is that hugeness. In other words:

What is your startup trying to do?

Where are you heading?

Why?

It should be big; it should be bold; it should be audacious. But it’s not be immediately measurable — if it’s measurable at all.

Within that big, hairy, audacious goal (BHAG), are smaller, more meaningful goals that are part of our theory or credibility:

Getting in front of early adopters efficiently;

Achieving rapid user growth;

Maximising retention and LTV;

etc.

These may look more specific for your startup, but it should still big something and immeasurable — and audacious.

As a thought experiment, let’s go with “rapid user growth” for a seed-stage SaaS company with a freemium offering. We need to demonstrate market potential and viability (credibility), which is crucial for attracting further investment and scaling the company.

In the early days, we can’t just measure our customer acquisition rate. At one point, it’s zero. Once it’s no longer zero, it spends quite a while functionally zero.

“We tripled our user base last month, and doubled it the month before! (*whispers* we have 12 customers)”

Since we can’t measure it directly…

2/ What are the signals you’re on the right track?

The problem with a big goal is that it’s big — we can’t just “achieve” rapid user growth.

Honestly, that’s not a thing. The chasm is too wide to cross.

Think of it like an explorer in the wilderness. There’s a far-off mountain you’re trying to get to, but you can’t just leap there. It’s not a walk; it’s an expedition. It’s dangerous. It takes days or weeks or months.

Often, you can’t even see the mountain through the dense forest foliage.

So you have to look for signals that you’re on the right track:

Is the river bank still to our right?

Are the stars oriented to our destination?

When we can see it, is the mountain getting larger?

etc.

Similarly, your job as an entrepreneur is to find the signals that you should be seeing if you’re getting closer to your mountain — to your goal.

(It's not necessarily one signal btw)

If you’re looking to rapid user growth, but you have yet to create demand in the market, then growth itself is a lagging indicator of progress.

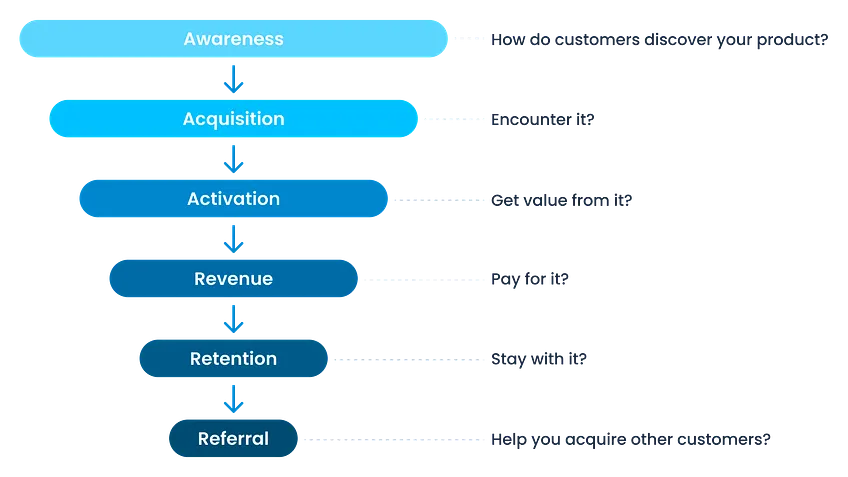

To oversimplify:

You can’t get revenue without customers signing up;

Customers won’t sign up if they don’t hit your landing page;

They won’t hit your landing page if they don’t click on your ad;

They won’t click on your ad if they don’t find it compelling;

They can’t find it compelling if they’re not the right customer;

etc.

These are a chain of signals that lead toward the ultimate goal. We can’t get there without them, and measuring them lets us know if we’re still oriented toward the mountain.

Based on your current stage, you might be one step removed from measuring revenue directly — or you might be 5 or 10.

Regardless, your goal is lagging indicator of what you’re accomplishing today. Focusing on measuring the goal itself will cause you to learn far too late (and far too expensively) that you’re on the wrong track.

That’s like picking a direction and taking a blindfolded march for a week, just hoping that you’re a lot closer to the mountain.

If you picked wrong, you lost 5 days — or more!

Instead, chain indicators together, starting at the revenue target and working backward, until you find a signal that you can see and meaningfully measure right now — even if that’s just “customers are seeing our message”.

For our example seed-stage startup with the rapid user growth goal, let’s say the right thing to measure right now is freemium conversions on a landing page.

We already know:

Who our early adopters are;

That we can reach them on social media; and

They resonate with our value proposition (clicks).

But these are freemium conversions. We don’t know:

To what degree they’ll convert to premium;

What the right premium pricing is;

How long they’ll stay;

etc.

We need them to reach our rapid user growth goal, but they’re functionally zero right now.

If we try to measure a lagging indicator, like revenue in this example, we might completely and dramatically miss the mark while still making incredible forward progress!

In fact, this is a really common problem for founders with investors. Founders communicate the wrong metric, they miss it, and they're stuck trying to justify the great progress they made anyway. But it just seems like backpedaling to the investors.

But once we have a meaningful signal…

3/ How do you measure those signals?

Honestly, most of the hard goal-setting work is already done.

What is a harder question than how.

By the time you get to metrics, you know what to look for. Now you just have to figure out how to measure it.

This is where specificity comes into play — where you make the metric discrete, precise, and targeted.

Metrics should be discrete.

What’s one thing you can measure that would indicate you’re seeing the signal?

If your signal is “customers are out there”, then it could be ad impressions or LinkedIn messages sent.

If it’s exposure to your value prop, it could be landing page visits, time spent of the site, video watch duration, etc.

What can you measure right now that would show the signal?

In our example, the discreteness of our signal works itself out. We’re looking for the number of people who didn’t have an account before, who sign up for a free one, subsequent to and immediately following a visit the landing page.

That said, if our signal was value prop resonance on LinkedIn, we’d still have more definitional work to do (ad vs organic; type of engagement; etc) to get the discreteness we need.

Metrics should be precise.

With one thing identified, get specific about it.

Document the who, what, when, and how clearly. Measurement is not the time for ambiguity.

If your metric is ad impressions:

What is the ad/copy?

Who will see the ad?

Where is it placed?

When will it run?

etc.

In our example, we’re tracking the number of those people who click the big blue “Start for free” button and log in with their email address. We’ll measure over the period of one week, and we’ll drive the traffic to the landing page through a particular set of planned organic posts on LinkedIn.

Boom.

Metrics should be targeted.

Without a specific target, data is just noise.

With a measurement clearly defined, you need to specify what success looks like. What is a good value? What’s a bad value?

You should never just “see what happens”, though it’s a mistake we all make — even me.

You want to pick a target that will unambiguously be a success or a failure — black and white, because grey sucks.

There is a science and art to picking these targets, but the general idea is that you want to base it on the theory of your startup. When you’re wrong, you want to force yourself to ask, “what does this mean?”

For most standard startup signals, you can look to pirate metrics.

When you put together the model of your startup (the “theory” in your credible theory of hugeness), you should be putting some back-of-napkin guesses to each pirate metric to ensure the math of your startup works.

These numbers are wrong. That’s not the point.

The point is that when we measure them and miss, we can revise our model and see if it still works — and to what degree it works. Is it still worth pursuing?

Then we revise the model.

And that’s the full cycle!

The goal is to get to a metric you can measure TODAY, which gives data on the next most important question to ask.

To recap:

Pick a big, immeasurable, audacious goal.

Find signals that will let you know you’re on the right track.

Run experiments on (i.e. measure) those signals.

Ask, “what does this mean”?

Revise the model; rinse and repeat.

Go forth and do likewise.

And that’s it for this week. Leave a comment and let me know what your most important goal, signal, and metric is right now in 2024.

I’ll see you next week.

—jdm

I just listened to your entire article. I was completely jazzed in the beginning - thinking “this is just what I need, I’m ready, I’m working” but as I listened more I got lost in the weeds. Everything you said sounded true, but my brain kept saying, “where is the model to accomplish this? Where is the canvas to fill out?”. So now I’ll look through the article for clues of what I have missed to implement this. I’ll keep going. I need to accomplish this. (So that’s my comment)